At the end of 19th century a new interest in musclebuilding arose, not muscle just as a means of survival or of defending oneself; there was a return to the Greek ideal-muscular development as a celebration of the human body.

This was the era when the ancient tradition of stone-lifting evolved into the modern sport of weightlifting. As the sport developed, it took on different aspects in different cultures. In Europe, weightlifting was a form of entertainment from which professional strongmen emerged-men who made their living by how much weight they could lift or support. How their physiques looked didn’t matter to them or to their audience. The result was that they tended to develop beefy, ponderous bodies.

In America at this time, a considerable interest in strength in relation to its effect on health developed. The adherents of physical culture stressed the need for eating natural, unprocessed foods-an idea that took root in response to the increasing use of new food-processing techniques.

Americans were beginning to move from farms and small towns to the cities; the automobile provided a new mobility. But at the same time, life was becoming increasingly sedentary, and the health problems that arise when a population eats too much of the wrong food, doesn’t get enough exercise, and exists in constant conditions of stress were just becoming apparent.

The physical culturists were battling this trend with a belief in overall health and physical conditioning, advocating moderation and balance in all aspects of life. The beer-drinking, pot-bellied strongmen of Europe were certainly not their ideal. What they needed was a model whose physique embodied the ideas they were trying to disseminate, someone who more closely resembled the idealized statues of ancient Greek athletes than the Bavarian beer hall bulls of Europe. They found such a man in the person of Eugen Sandow, a turn-of-the-century physical culture superstar.

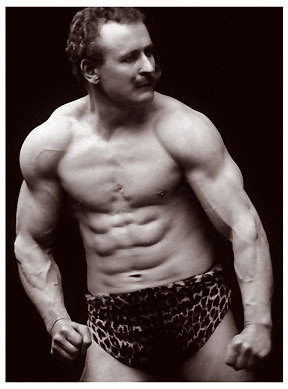

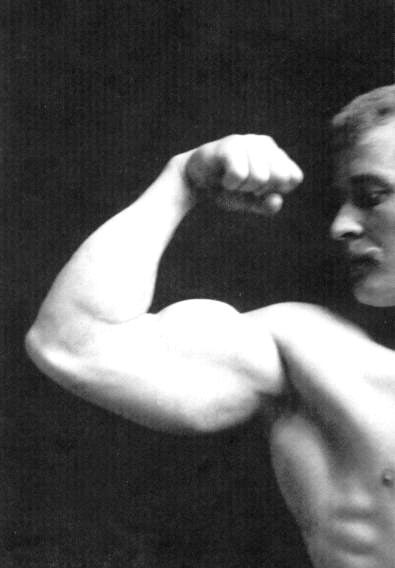

Sandow made his reputation in Europe as a professional strongman, successfully challenging other strongmen and outdoing them at their own stunts. He came to America in the 1890s and was promoted by Florenz Ziegfeld, who billed him as “The World’s Strongest Man” and put him on tour. But what really set Sandow apart was the aesthetic quality of his physique.

Sandow was beautiful, no doubt about it. He was an exhibitionist and enjoyed having people look at his body as well as admire his strongman stunts. He would step into a glass case and pose, wearing nothing but a fig leaf, while the audience stared and the women oohed and aahed at the beauty and symmetry of his muscular development. This celebration of the aesthetic qualities of the male physique was something very new. During the Victorian age men had covered themselves in confining clothing, and very few artists used the male nude as a subject for their paintings.

Due largely to Sandow’s popularity, sales of barbells and dumbbells skyrocketed. Sandow earned thousands of dollars a week and created a whole industry around himself through the sale of books and magazines.

Contests were held in which the physical measurements of the competitors were compared, then Sandow awarded a gold-plated statue of himself to the winners. But, ultimately, he fell victim to his own macho mystique.

It is said that one day his car ran off the road and he felt compelled to demonstrate his strength by single-handedly hauling it out of a ditch. As a result the man whom King George of England had appointed “Professor of Scientific Physical Culture to His Majesty” suffered a brain hemorrhage that ended his life.